What's in a Fastball: How a 4-Seamer Becomes Elite

By Matthew Duston | March 5, 2020

For all the love nasty sliders, curves, and changeups get in baseball, in the end, the fastball is still the most celebrated - everyone has one, and if you don’t have a good enough one you don’t make the majors. And for fastballs, speed is king - stadium boards light up with fire as their pitchers reach 100+, and the hardest throwing pitchers often end up the best relievers, like Mariano Rivera and Jordan Hicks. But for all the attention that velocity gets when talking about fastballs, many other factors go into making a fastball more effective, and with information from MLB’s statcast over the past 5 years, fastball effectiveness is now more quantifiable than ever before.

This can especially be seen in spin-rate, which has become more accessible than ever before with MLB’s statcast. Spin-rate is sometimes considered more predictive of SwStr% than velocity, which makes sense considering that it effectively details how much a ball is moving in the air after being thrown. Let’s take a look at the SwStr% for different rates of velocities and spin-rates for 4-seam fastballs.

As we can see, spin rate and velocity have a significant impact on the swinging strike rate, and therefore the effectiveness, of a fastball. Velocity, as expected, correlates strongly with SwStr%, and so does high spin-rates. As for pitchers with the lowest spin rates, having a low spin-rate fastball doesn’t preclude success, it just does so in a different way. Out of the 12 pitchers who threw 100 or more 4-seam fastballs in 2019 with spin rates below 2000, only one had a true swing-and-miss fastball, Sean Manaea, who allowed an elite .225 wOBA and a 24% whiff rate on the pitch with only 1954 rpm. The others performed significantly worse, averaging a 0.410 wOBA as a group. It’s still possible to be successful with a low spin rate – pitchers like Hyun-Jin Ryu are able to maintain success with high-quality breaking pitches, and less rising action means that many ground-ball pitchers have low spin-rate fastballs whose effectiveness isn’t captured by SwStr%. Still, in the end, if a pitcher is trying to strike a batter out, a high spin-rate fastball is the best bet.

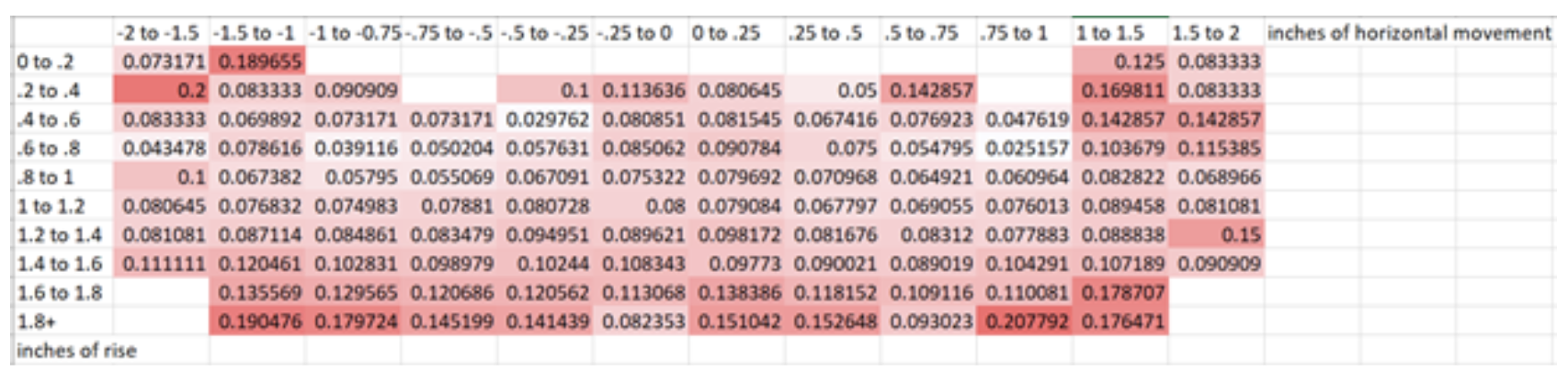

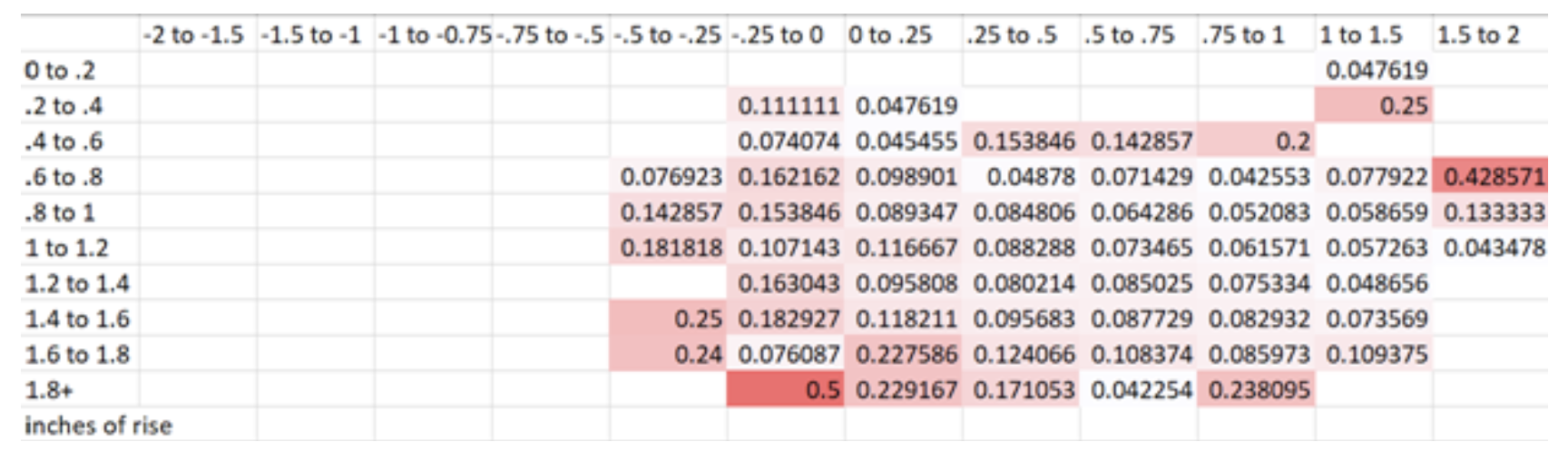

Spin rate has multiple different effects, and spin axis can affect the direction and when a ball moves, which both can have major impacts on the effectiveness of a pitch. However, we can look at a simplified way to show how spin-rate affects the trajectory of a pitch by seeing how much a pitch has moved from the pitcher’s release point to where it crosses the plate, using data collected by statcast. Below is another plot of swinging strike rate, this time using inches of horizontal movement, or break, as the x-axis, and inches of vertical movement, or rise, as the y-axis.

As you can see, the more movement a pitch has, the more effective it is, which makes sense considering that movement is heavily impacted by pitch velocity and spin rate. A few details stand out, however – for one, vertical pitch movement impacts swinging strike rate significantly more than horizontal movement. This can be explained, however, by the second observation – horizontal movement goes from -2 to +2, and is almost completely influenced by handedness. Pitcher and Batter handedness can have a significant impact on how a pitch will look in different situations, and so let’s split the data up by matchup.

These give a much clearer idea of the impact horizontal movement has on swinging strike rate, and it’s clear that no matter the handedness, a batter is more likely to whiff on a fastball the more it moves away from them. From this, vertical movement, spin-rate, and velocity, we should now have a good idea of how these metrics affect the effectiveness of a fastball. Now let’s take a look at how one of the better 4-seam fastballs in the league measures up.

Gerrit Cole is considered one of the few aces in the league, and much of his success is contributed to his high-quality fastball, which averages 97 mph and 2350 rpm, both elite measures for a starter. As for movement, Statcast provides a handy visual of the average pitch movement for all pitchers in the MLB, so let’s look at where Cole sits on it.

Unsurprisingly, he’s near the top of both horizontal and vertical movement - however, as we saw above, pitches with the same movement can have vastly different results depending on the handedness of whoever’s in the batter’s box. So how does his right-breaking fastball do against batters from both sides of the plate? Although Cole is a righty himself, his fastball is mediocre against other righties, with only a 28.2% whiff rate, and allowing a .274 wOBA. Cole is still able to throw it 49% of the time though, largely thanks to his best secondary pitch, his slider, which he uses 31.8% of the time against righties to great success, allowing only a .217 wOBA, and a 42.2% whiff rate.

Against lefties, his slider is less effective, with a .234 wOBA, still good, but forcing him to rely more on his curveball, and especially his fastball, which he throws 4% more. This is because, against lefties, his fastball truly shines, with a .243 wOBA, and a whopping 43.8% whiff rate. Cole’s fastball is elite, but even with that whiff rate, he still allowed a .243 wOBA on the pitch - still worse than his secondaries. No matter how good the fastball, Cole needs his secondaries to remain elite in order to avoid hitters sitting on his fastball, and to make himself a complete pitcher. To help illustrate this, let’s take a look at another pitcher with almost the same movement, but completely different results

Oliver Drake is a 32-year old reliever, currently a lefty specialist with the Rays. His fastball appears average at first, with a 2146 rpm spin rate, and a 93.5 mph average, which would put him right around MLB average for both pitches. Drake is somewhat interesting because he’s a right-handed pitcher who’s a left-handed specialist, meaning he has reverse splits. This isn’t too unusual, but the way he manages it makes him one of the more unique pitchers in baseball. Remember where Gerrit Cole’s movement was compared to the rest of the MLB? Let’s see how Drake compares.

Drake has around the same vertical movement as Cole, and is around the same place as Cole on horizontal movement to the opposite side. Here’s where things get weird though - Drake’s whiff % on his fastball against righties is 37.4% - not as good as Cole’s, but still well above league average. So how did Drake become a lefty-specialist?

In 2019 against lefties, Drake only threw his fastball 21.3% of the time, which is reasonable considering the 21.7% whiff rate on the pitch, but less so looking at the .175 wOBA it allowed. This is because his second pitch, his splitter, is even better against lefties. Drake threw it 42.5 percent of the time in 2019, for a .152 wOBA, and a 42.5% whiff%, explaining how he ended the year with a 0.30 ERA against lefties - it didn’t matter that his fastball wasn’t as effective, he just had to use it to keep hitters honest against his splitter. Which brings us to the 25.2 innings he threw against righty hitters in 2019.

Against righties, Drake only threw his splitter 45% of the time, understandable considering that he allowed a .401 wOBA on the pitch. His fastball meanwhile, as we mentioned before, had a 37.4% whiff rate, and so it makes sense that he threw it more than his splitter, at 54.8%. What makes less sense is the .348 wOBA he allowed on the pitch, leading to the 6.66 ERA he allowed against righties all year.

Even though Drake’s fastball has been better against righties than lefties, the splitters loss of effectiveness against righties makes much more of a difference. Against lefties, hitters swing at 53% of Drake’s pitches, many of them for whiffs, while against righties, hitters swing at only 47% of pitches. The most notable difference here is how hitters react to his splitter, as instead of whiffing, they identify the pitch better, and the percent of splitters thrown for a ball increases from 27% to 39% against righties. If hitters are able to identify the pitches better, they’ll be ahead of the count more, and therefore, no matter how good the fastball is, hitters will still have a better chance to see a pitch that they like, and perform much better than if they were facing another secondary pitch to keep them honest.

So with all of statcast’s data, as spin-rate is introduced more and more into baseball lexicon, and velocity continues to be displayed with every pitch, baseball has more data than ever to quantify how good a specific pitch is. But while gawking at the newest high spin-rate/velocity pitcher, it’s important to take notes from pitchers like Oliver Drake, and remember that a good fastball is still nothing without the right secondary pitches to back it up.