Should Guards be Posting Up More Often?

By Colin Rondon | December 10, 2024

Introduction

The post-up is a basketball move where the player faces their back to their defender and backs them down to create space for a close-to-the-basket hook shot or a fadeaway shot. This is often reserved for the big men like Shaquille O’Neal or Tim Duncan who are strong enough to push smaller players to get closer to the basket, and sometimes skilled shot-makers like Kobe Bryant and DeMar DeRozan.

This move has seen a steep fall-off in recent years through how frequently it is done. For the previous 2023-2024 NBA season, the average frequency percentage (Freq%) for the post-up for all NBA teams was just 4.17% Analytics have proven that any shot other than the 3-point shot or a shot at the rim are inefficient and not worth shooting. We saw this almost work with the 2018-2019 Houston Rockets (James Harden & Chris Paul) who unleashed 3 pointers 52% of the time, more than half of their shots, and made it to game 7 in the Western Conference Finals, where they missed 27 straight 3-pointers.

However, the skillset of NBA guards has expanded since the late 2000’s when the guard position evolved from the pure John Stockton role of prioritizing running the offense and setting up teammates with good looks, to the scorer-playmaker hybrids like Russell Westbrook or the pure scorers like Derrick Rose. Prominent guards in the league today are resurrecting the once frowned-upon post-up, whether it be last season's MVP candidates like Jalen Brunson, Shai Gilgeous-Alexander, Luka Doncic, or other prolific guards like Devin Booker and Anthony Edwards,.

This made me wonder if the post-up is a viable play for guards. You often see players resort to the 10-dribble combo at the end of the shot clock, ending in a step-back or contested three, but what if they tried posting up more so they could use their strength to back down a weaker or smaller defender and create space off of a fadeaway or spin into a post hook?

Data Exploration

In my data investigation, I found that not many guards qualified for Synergy’s restriction of both 10 minutes played per game and 10 possessions per play type to qualify, so I combined data from the previous 4 seasons (the 2020’s) to also use a K-means clustering model and attempt to find characteristics of a good post-up guard.

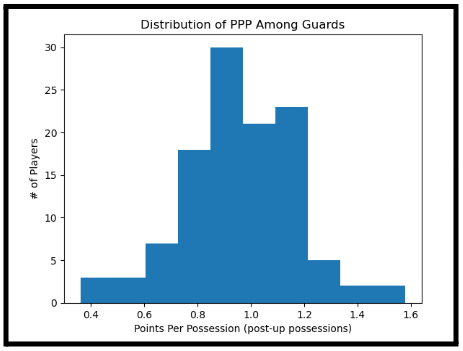

Let’s look at a few key statistics when it comes to efficiency for a specific play type: points per possession (PPP), frequency percentage (Freq%), and score frequency percentage (Score Freq%). The first statistic quantifies how much output a player gets from each post-up that they do, the second ensures we have some context when looking at how many points they generate through post-ups, and the third is a good summary of how much they convert on their post-ups in any way, whether it be a free-throw, and-one, or a regular 2-pointer. Keep in mind that this does NOT count assists that they may generate off of kick-outs from double-teams; the Score Freq% only considers points the player scores themselves.

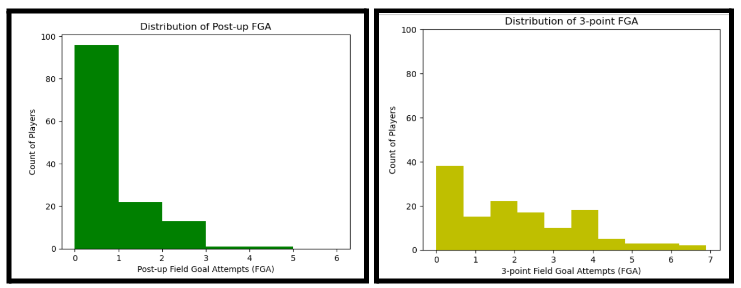

Looking at the histogram above, there are a good number of guards who can score an average of 1 point per post-up. In fact, the mean PPP of all guards in my dataset is 0.96, and that’s basically scoring on a post-up 50% of the time. That’s pretty good!

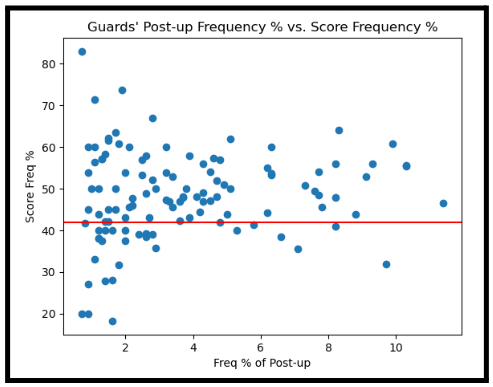

Although a lot of guards can score 42% of the time on post-ups, they don't do it often. We’ll look back at this later.

(Note: I used 42% as my threshold of “good” because a good 3-point shooter is usually set at 39% and above. Since it is a closer shot than the 3-point shot but can be difficult on turnaround shots, the threshold is only slightly above that of 3-point shooting.)

Characteristics of “Good” Post-up guards?

I want to investigate if there are any characteristics that stand out from “good” post-up guards. I’ll define “good” as >= 1.0 PPP.

First, we’ll look at the full distribution, then we’ll get into the K-means clustering process to look at any common characteristics.

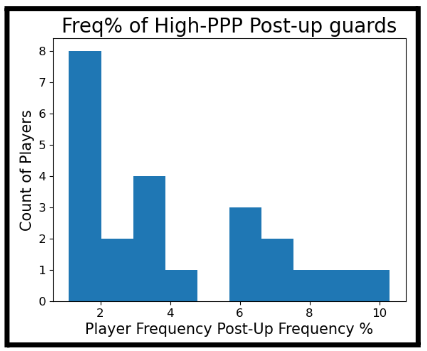

Unsurprisingly, many players are not getting many post-ups. We’ll look at this with more context later.

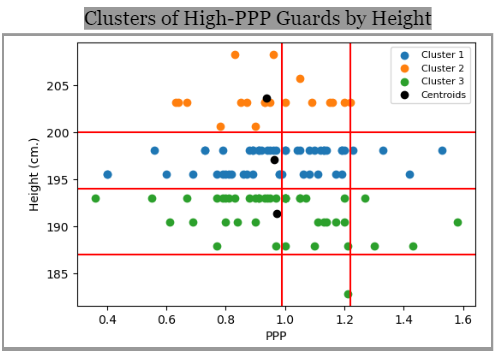

K-Means Clustering

I decided to divide the dataset into 3 clusters, firstly because my calculations suggested it would be a good number, and secondly, because I wanted to look at 3 different groups:

- Really short guards (green cluster)

-

a.) height < 195cm.

b.) or height < 6'4.75"

- The (approximately) typical-height guards (blue cluster)

-

a.) 195cm < height < 200 cm.

b.) or 6'4.75" <= height <- 6'6.75"

- And the tall guards (blue cluter)

-

a.) height >= 200cm.

b.) or height > 6'6.75"

- Devin Booker and Bradley Beal: the Phoenix Suns ranks 10th in the league with 5.0% post-up frequency with the help of Kevin Durant (9.2% post-up frequency, 92nd in the league)

- Anthony Edwards: the Minnesota Timberwolves ranks 8th in the league with 5.4% post-up frequency with the help of Karl-Anthony Towns (13.6% post-up frequency, 38th in the league) and Rudy Gobert (10.2% post-up frequency, 18th in the league)

- Mikal Bridges: he was the first option on offense for the Brooklyn Nets, who ranked last in the league in post-up frequency with 1.5%

The centroids, or the black dots which represent the average of each cluster, surprisingly show that the shortest guards are best at the post-up. Interesting!

Let’s look at both the blue and green clusters, the shortest guards and typical-height guards.

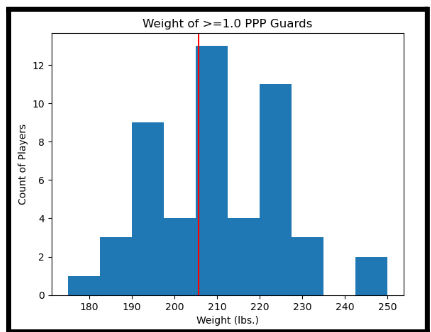

With the average weight of guards and guard-forwards averaging out to 205.60 lbs., it is unsurprising that the majority of the high-PPP guards on the “shorter” end are heavier than average. This might explain how a lot of Cluster 3 guards, the shortest ones in our dataset, are scoring better on post-ups then Cluster 2 guards: if they don’t have the height advantage, they have the weight advantage. If they can’t tower over their defender’s contest, they can push their defender to create enough space for an easier shot.

Let’s look at the top 12 PPP post-up guards from the 2023-2024 season that meet the criteria of our clusters of interest, blue and green:

Some expected names are here like DeMar DeRozan, whose bread-and-butter is the turnaround fadeaway, plus Devin Booker and Kyrie Irving who like that shot too. However, some surprising names pop up like De’Aaron Fox and Bradley Beal. Those guys are on the shorter end, and they aren’t first-to-mind for fadeaway or post-up shots. Unsurprisingly, a majority of these players (9 out of 12) are over 200 pounds.

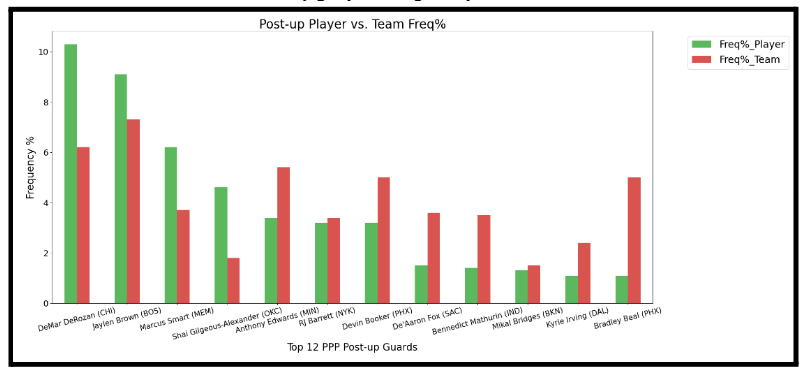

Now, let’s look at how often these players do the post-up compared to how much their team does, with the bar chart sorted by player frequency %:

As expected, the majority of these players do the post-up less than their teams run it. Why might this be? Among this majority are players who are on teams that have better post-up personnel like

Meanwhile, the other players are on teams that don’t have the personnel or have stars who the coaches think aren’t fit for the move, and therefore shy away from the post-up in general:

For context. the highest post-up FREQ% is by the Denver Nuggets with 7.8%, who have Nikola Jokic, a master of the post-up.

If teams don’t run the post-up so much, how much do the players value it, especially compared to other types of shots like 3-pointers, mid-rangers, and paint shots?

Shot-Type Analysis

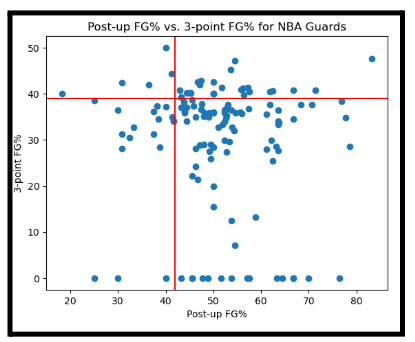

Returning to the introduction, let’s do a comparison of 2023-2024 NBA guards’ post-up field goal percentage (post-up FG%) versus their 3-point field goal percentage (3FG%).

There are 4 sections in this graph divided by the 39% 3FG% and 42% post-up FG% lines, and we can see that the bottom right one, the one where 3FG% < 39% and post-up FG% > 42%, is where the majority of NBA guards fall. At the surface-level, this looks like the post-up is a better option than the 3-pointer, but as proven below, because so many more players take more 3-pointers than post-ups (91 in the dataset) compared to how many take more post-ups than 3-pointers (41), we can’t conclude here just yet.

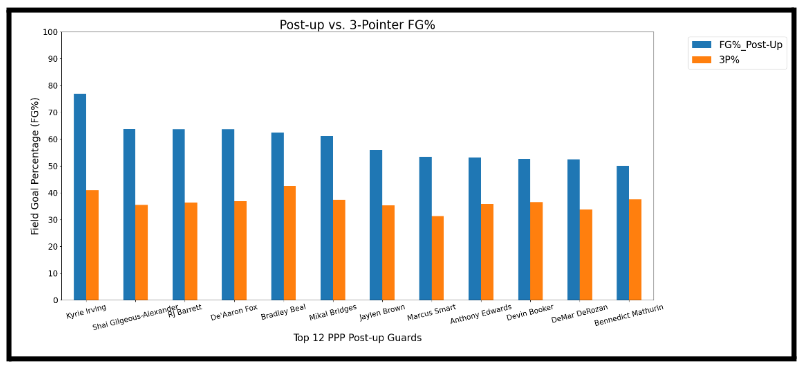

Let’s do the same comparison but for the top 12 high PPP post-up guards of 2023-24:

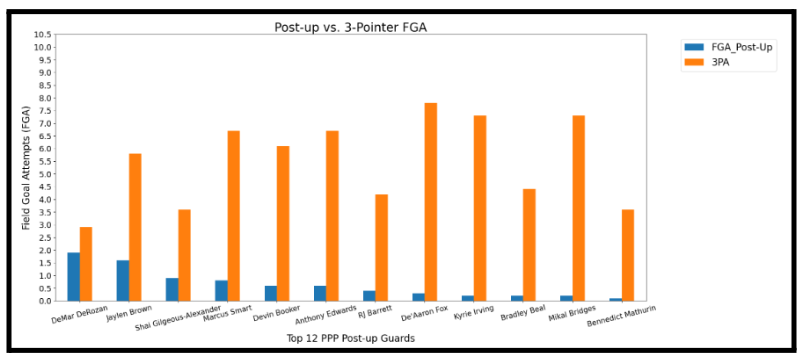

As shown above, all of these players have a much higher post-up FG% compared to that for 3-pointers. Does that mean the post-up is a way more viable shot than the 3-pointer? No. When we look at the chart below, we might see why there’s this disparity in field-goal percentage:

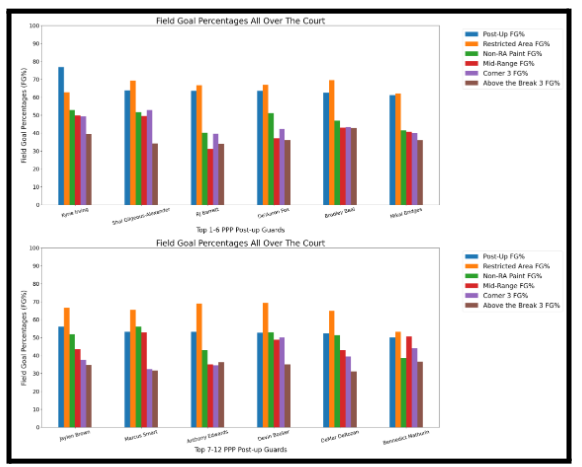

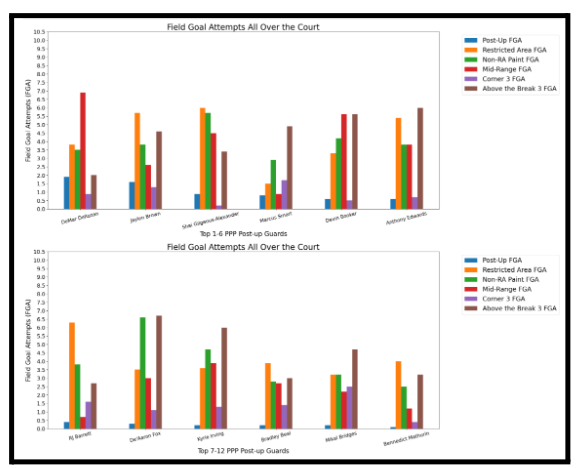

Now, let’s look at this data together with their percentages and attempts for all other types of shots (looking at their shot diets). For context, the restricted area is the half-circle under the hoop, and above the break refers to 3-pointers taken anywhere other than the corners

As expected, their paint field goal percentage is the highest since that is the closest shot to the hoop, but, a majority of these players have their second-best field goal percentage in their post-ups (a few only slightly higher or lower to that of non-RA paint shots). For how much they shoot 3-pointers at a lower rate, even if it’s one extra point, maybe they could diversify their shot diet more. Let’s look at their attempts all over the court:

These shot diets show that there is hope for analytics not purely dominating the NBA, since DeMar DeRozan, Shai-Gilgeous Alexander, RJ Barrett, and Devin Booker don’t have their 2nd-most shot-type attempted as the 3-pointer. But, they all still rarely rely on the post-up, with it being their least-taken shot other than the corner 3 for a few. Looking at how efficient these players are at the post-up, maybe they could diversify their shot diet.

Implications and Possible Improvements

Now, although we’ve proved that the post-up can be a useful skill for guards, this obviously only applies to the strong guards that have the green light from their coach. Many of the names of high-PPP post-up guards are superstars or second options that the coaches rely on to score.

The post-up can slow down the game, which is what most teams might not want. However, it can generate good mismatches or kick-outs for open shots. Plus, when you see how many difficult 3-pointers players choose to take over posting up, a less predictable move that has the potential to create them more space, this is a skill that guards should develop when they develop or have the muscle. This investigation was not meant to prove the post-up should be the primary choice for the play to run every possession, but that it is a useful skill for guards to pull out of their bag when necessary, which is more often than you might think.

This investigation could be improved by creating more calculated thresholds for what a “good” post-up field-goal percentage is, as well as looking into more context like the personnel and play-style that each team has that could lead to high or low post-up frequency percentages.